We are Still People of the Corn

Maíz Narratives, Indigenous Pedagogy, and Ancestral Memory

“I don’t want to hear your philosophy if you can’t grow corn.”

–Winona LaDuke

Growing up as a child in the Eastside of Los Angeles, I was privileged to bear the fruits from the early struggles of the Chicano Movement that took place in the generations before me. Within the harvest from decades of sowing and community organizing around my local neighborhoods, was a path for urban brown youth, like me, to reconnect to our ancestral cultures. I grew up with a Xicana mother and a Colombian father, and have so-called “mestizo” roots from West Texas, Northern and Central Mexico, and the Colombian Andes. The oral stories of my maternal family trace our Indigenous ancestry to the Jumano and Rarámuri peoples of the Chihuahuan Desert, yet due to assimilationist policies, we have been disconnected from that lineage. Having a sense of identity is crucial to having a sense of belonging to the world. The colonial project has worked hard at disempowering countless communities, which I believe is the root to the trauma and dysfunction existent in many oppressed peoples. Patrisia Gonzales, healer and Chicano and American Indian Studies scholar, states that “de-Indigenization is reversible. Reclaiming the power to tell and retell our stories of relationship is a function of the principle of regeneration” (2012, p. 226). The reclaiming of self-determined stories, cultures and identities is important for the healing of oppressed and colonized peoples.

In this essay, I center the story of corn as a decolonial tool of reclaiming one’s identity and using storytelling and art as an Indigenous pedagogy of community transformation. I use the Indigenous-based research in the scholarship of Roberto “Dr. Cintli” Rodriguez’s work, Our Sacred Maíz Is Our Mother: Indigeneity and Belonging in the Americas, as an anchor that explains the importance of corn in many cultures throughout the American continent. From a young age, I learned about my cultural community being gente de maíz, people of the corn. The neighborhoods that raised me immersed me in the symbolism and archetypes of Mesoamerican creation stories painted onto countless murals. From corn fields to corn gods, these images were deeply engrained into me and continue to inform my sense of identity. From this cultural awareness, I developed a social art practice in collaboration with peers to teach others how to make corn husk dolls as a way to awaken my community’s collective consciousness about our ancient relationship to corn. Through the experiential learning of making the dolls, participants are immersed in the cultural history of corn through the telling of creation stories and facilitating dialogue. Indigenous educational pedagogies are participatory and “life-centered,” in contrast to the top-down nature of traditional forms of Western education. Cajete explains “life-centered” education as a “transformational process of learning by bringing forth illumination from one’s ego center” (2020, p. ix). Through culturally rooted experiential learning, like the practice of making corn husk dolls, one can find self empowerment and recuperate ancestral memory through reclaiming their cultural identity. Colonial logics do not make room for the ways cultural resurgence takes place, yet Indigenous worldviews understand “the principle of regeneration” and that ancestral memory can be a door to healing and coming back to power.

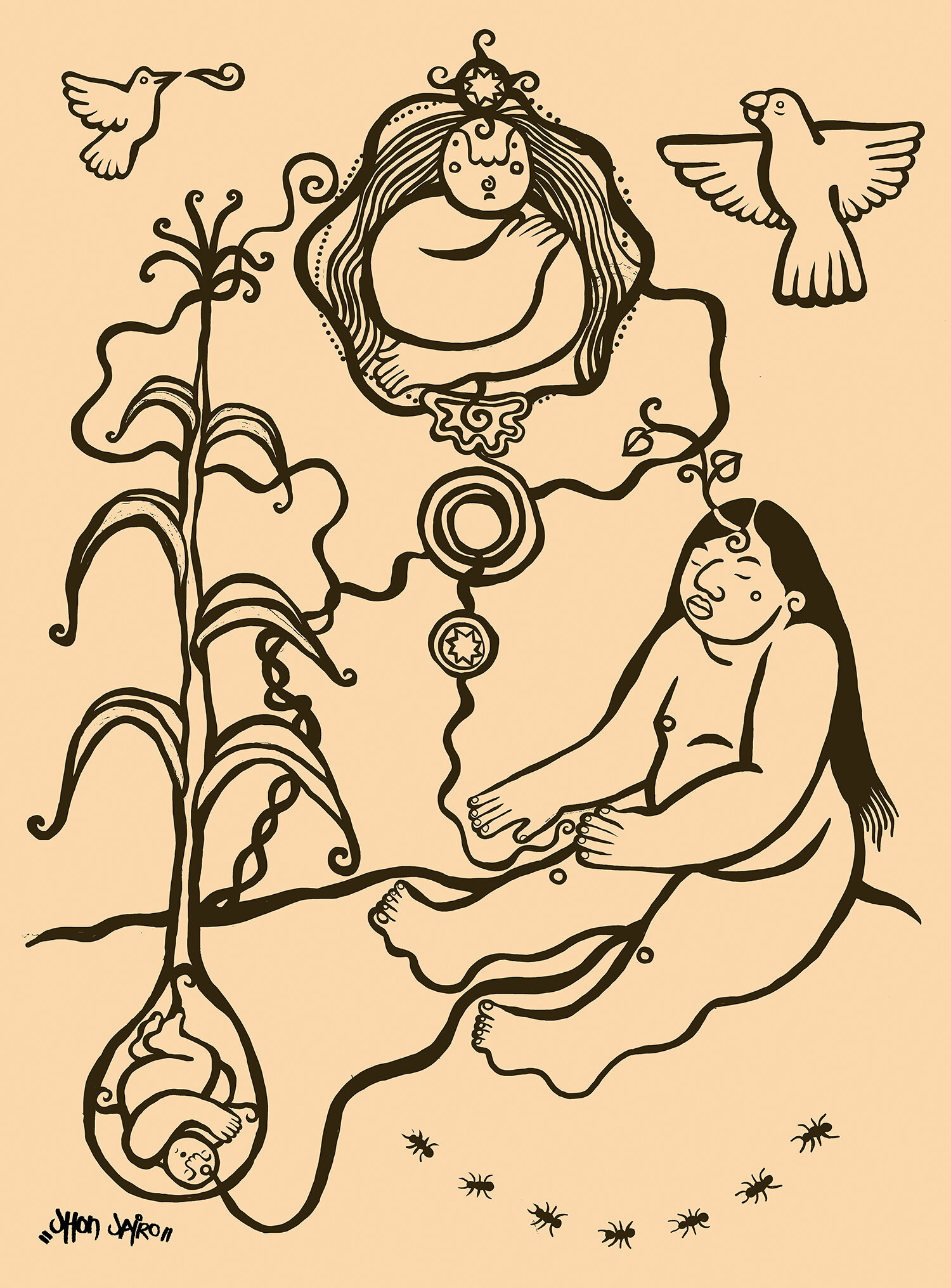

Maíz Narratives (2019) by John Jairo Valencia, depicting the origin story of Quetzalcoatl and the Ants gifting human beings maíz.

• Origin Story

In the early morning a few months out of the year, I am able to trace the planet Venus as it looms above the rising Sun in the East. My morning prayers towards the Sun during these moments includes an acknowledgment of this astronomical phenomenon. I give thanks to the Sun for bringing forth a new day and to the Morning Star for reminding me of the opportunity of new beginnings. If one is to be observant of this celestial movement, they would become attuned to the way that Venus has its own calendrical cycle. According to Anthony Aveni, anthropologist and one of the founders of the field of archaeoastronomy, “Venus is by far the most important planet” in Mesoamerican cosmology, as well as other Native American cultures (2001, p. 38). One of the few remaining pre-colonial books of the Maya that survived the book burnings from the Spanish friars, the Dresden Codex, contains an extensive mathematical table documenting the astronomical cycle of Venus. In one of its pages, calculations for the number 584 is able to be identified, which modern astronomers have matched with the 583.92 days of Venus’s synodic period (2001, p. 186). The mythological impulses of the human psyche are bound to orient themselves to the brightest planet in the sky.

Countless cultures throughout the world have documented the dance of Venus between the eastern and western horizons through the oral tradition, creation stories, and ancestral sciences. These cosmological orientations are what anchor a people to their interconnected relationship with the universe. In Nahua cosmology, the creation of the world is marked through the Venus cycle, as the planet role plays the journey of Quetzalcoatl. Quetzalcoatl is one of the creator beings responsible for the creation, destruction, and recreation of the several eras or “Suns” of the world. In Western interpretations of this creation story, it is accepted that “at the time when the planet was visible in the sky (as the evening star) Quetzalcoatl died” (1904, p. 364-5). The oral histories of the Aztec Dance tradition describe a more philosophical meaning to the so-called “death” of Quetzalcoatl. Venus’s setting in the West as the evening star embodies Quetzalcoatl’s journey into Mictlan, the place of the ancestors in the underworld, in order to forge the world we are currently living in. As Quetzalcoatl spent time in Mictlan, bones from the previous era were collected in order to be used to create the human beings of today. In Quetzalcoatl’s ascent back into the upperworld, the current era of the “Fifth Sun” began. This re- creation of the world is marked in Venus’s re-emergence as the Morning Star in the East.

Multiple stories that describe the early experiences of the first humans follow this ascent of Quetzalcoatl. One of the stories that is foundational to the development of corn cultures in the Americas is how Quetzalcoatl decided corn to be the first food for the newly created humans. Roberto “Dr. Cintli” Rodriguez, recounts the origin story of corn in “The Ants of Quetzalcoatl” as told by the Nahua community of Amatlán in the Mexican State of Morelos. At the dawn of the Fifth Sun, Quetzalcoatl was tasked with searching for sustenance for the people. While walking along, “Quetzalcoatl notices red ants carrying kernels of corn,” and asks one of them “What is that on your back?” In the dialogue between the ants and Quetzalcoatl, corn was eventually exchanged. Queztalcoatl took the kernels of corn to one of the cosmic realms called Tamoanchan where the “Lords [...] approve of it as food for the people” (2014, p. xviii). The relationship between the cosmos, the earth, and human beings are intimately tied through the storytelling traditions of Indigenous cultures. The intimate relationships between human beings and corn is highlighted in this creation story and many more throughout the Americas.

• • Cultural History

Rodriguez theorizes that the major civilizational impulses in the Americas were catalyzed by the early ancestors who built relationships with corn over 7,000 years ago. The development of the sacred calendrical counts, advanced mathematics, astronomy and the building of the pyramids may have been inspired by the ancient scientific observations of corn. The ancestral mathematics of Mesoamerican cultures observed sacred numbers that are present in nature, such as 20 (fingers and toes), 13 (moon cycles in a solar year), 0 (origin). In the sacred calendrical cycle of Mesoamerican cultures, the combination of 20-day symbols with 13 numerals create the 260-day sacred calendar. The number 260 is considered the “count of the human being’s fate and ceremonial count of maize” (Lara, 2013, pg. 43). The 260 day cycle is the estimated time period of human gestation in the womb, relates to the ceremonial cycle of growing corn, and roughly coincides with the 263 days Venus appears as either the Morning or Evening Star. It is possible that these observations were made when humans began to cultivate corn, which laid the roots for the advanced scientific and philosophical knowledge that emerged from the Americas.

The telling and remembering of these stories amongst de-indigenized peoples of the Americas serves as a site of empowerment and healing from the wounds of the colonial project. Rodriguez’s work seeks to highlight the ways that Indigenous corn culture continues to be resilient in the lives of peoples of Mexican and Central American origin. Rodriguez calls the oral stories and ceremonial practices “maíz narratives,” which he argues can regenerate Indigenous identity and consciousness. The work of the late Mexican anthropologist, Miguel Bonfil Batalla, Mexico Profundo, provides a rich analysis of Indigenous cultural continuity in the majority of the Mexican population. In one of his examples of continuity, he states that “Corn continues to be the principle crop, along with other products of the milpa” (1996, p. 44). The majority of the Indigenous foodways in communities throughout the continent, from the South American Andes to the Eastern Woodlands of North America, still revolve around corn.

The colonial project in the Americas sought to rid itself of anything that was “Indian” in order to make way for the imposing settler-culture. The processes of colonization in the Americas took place both physically and psychologically; Bonfil-Batalla states that “de- Indianization, has been called ‘mixture’ [mestizaje], but it really was, and is, ethnocide” (1996, p. 24). The psychological impacts of ethnocide continuously affects both Indigenous and so-called “mestizo” communities through internalized racism that creates subliminal messaging that encourages the social distancing from ancestral cultures. The colonial project did and continues to do its job in erasing many communities’ connection to Indigenous cultures; this can be seen in the extinction of countless Indigenous languages, the demonization and criminalization of spiritual practices, and the displacement from ancestral lands. The processes of “de- Indianization” and “mestizaje” as forms of assimilation enforces white supremacy through promoting lateral violence towards markers of indigeneity (e.g. dark skin, traditional clothing, etc.); often times this division is perpetuated even within families. Regardless of the systematic attempts of erasing people’s indigeneity, corn continues to be an essential part of the majority of cultures across the continent, in both Indigenous and “mestizo” communities.

Because the colonial project was so successful in promoting the disidentification with Indigenous ancestry, the reclaiming of “maíz narratives” within de-indigenized communities is a powerful action of decolonization. The concept of being gente de maíz is not just a mere saying. If one is to look deeply into the cosmology that anchors the Native Sciences of much of the “American continent,” one will see how following the corn can awaken much deeper knowledges that will give insight of who we are as human beings. Rodriguez asks us: “If people are not part of tribes of clans and if they no longer grow, harvest, and partake in ceremonial activities, can they still have a connection to their ancestral maíz cultures?” and “Is knowledge of maíz narratives [...] enough to maintain that connection? Are new stories needed?” (2014, p. xxvi). These questions have incited in me the desire to develop transformative practices that utilize storytelling as a from of regenerating connection to ancestral cultures. Because of this, I have developed a social practice of art in teaching people how to make corn husk dolls, which I believe have the power to inspire social consciousness and heal intergenerational trauma.

• • • Indigenous Pedagogy

My practice of making corn husk dolls emerged from a week-long political and cultural teach-in I helped organize in 2013 with other students part of Xinaxtli, a student-led organization at UC Berkeley. During the week of Indigenous Peoples Day, we organized a series of workshops dedicated to our relationship with corn. We invited members of our local Aztec Dancing group, In Xochitl In Cuicatl, who had learned how to make corn husk dolls from the Chicano Studies Department’s maestra artist, Celia Herrera Rodriguez. Since then, I have adopted this teaching and developed curriculum around it in order to immerse participants in the story of corn. In my 7 years of practice, teaching diverse groups of people, I have witnessed how experiential learning and playing with corn material (i.e. seeds, husks, cobs, masa) can recuperate ancestral memory. Through the creation of the corn husk dolls, I take a somatic approach to storytelling by inviting an exploration of the senses. As participants are seated in a circle, I ask them to touch, taste, smell, listen to, and observe the corn material laid out in an altar in the center. As participants engage their senses, I include the storytelling of creation stories, such as “the Ants of Quetzalcoatl,” parts of the Popol Vuh of the Quiché Maya, and the teaching of how our ancient human ancestors 7,000 years ago genetically engineered the wild teosinte into the hundreds of varieties of domesticated corn we have today.

Through this practice, I invite participants to remember their relationship with corn, and facilitate the storytelling of our collective “maíz narratives.” In response to Roberto “Dr. Cintli” Rodriguez’s questions mentioned earlier, I do believe that new stories are to be told in order to maintain connection to one’s ancestral culture. These new stories are to emerge from descendants of corn cultures rebuilding their relationships to the plant. I am reminded of the concept of “tribalography,” introduced by Choctaw scholar LeAnne Howe, which she explains is a rhetorical space where “Native people created narratives that were histories and stories with the power to transform” (1999, p. 118). Howe describes how Native stories influence both tribal and national narratives, and that the lived stories of Native people today are the embodiment of tribalographies. In this respect, I propose that within each respective community, including de- indigenized peoples, each generation has the power to continue narrating their evolving creation stories. In applying this concept to the facilitation of collective storytelling around corn husk dolls, participants bring up memories that they have had with their families, such as helping to make tamales during Christmas-time or their grandparents’ cooking. Remembering something as simple as food, an ancestor, a smell are vital pillars which become the stories that will strengthen the continuation of our collective corn culture. In respects to the foundational texts of Indigenous-based research, Linda Tuhiwai Smith reminds us in Decolonizing Methodologies that storytelling is an essential project of Indigenous research and states that “new stories contribute to a collective story in which every indigenous person has a place” (1999, p. 145).

Storytelling is central to Indigenous pedagogies of teaching and transmission of culture. Paulo Freire discusses the “banking” concept of education in his work Pedagogy of the Oppressed, a systematic form of teaching that does not give students in oppressed communities agency to self-determine their own realities. The “banking” concept of education is the epitome of the top-down methods of colonial education that denies students the opportunity to critically think or contribute their own intelligence. Freire states that this type of paternalistic relationship of teacher-student “tend[s] in the process of being narrated to become lifeless and petrified,” where “The teacher talks about reality as if it were motionless, static, compartmentalized, and predictable” (2000, p. 71). In this dynamic, students are also denied their own relationship to the subjects they are learning; especially Indigenous students whose existences are erased within colonial education systems. Gregory Cajete, Tewa Scholar, states in the prologue of the anthology of essays in Native Minds Rising that “Educating and enlivening the inner self is the life-centered imperative of Indigenous education embodied in the metaphor, ‘seeking life’ or for ‘life’s sake.’ Inherent in this metaphor [of ‘seeking life’] is the realization that ritual, myth, vision, art and learning the ‘art’ of relationship in a particular environmental context facilitates the health and wholeness of individual, family, and community” (2020, p. ix). The process for colonized peoples to come back to power will take lots of creative approaches to education, which allows for community transformation. Experiential learning, storytelling, and cultural arts are powerful tools to transform colonial logics and oppressive systems that have disempowered countless groups of people.

Series of corn husk doll and storytelling workshops done in collaboration with Hood Herbalism, The Cultural Conservancy, La Comunidad Ixim, and Sisters of South LA, in Los Angeles and San Francisco, CA, 2016-2019.

• • • • Awakening Ancestral Memory

In this practice, there are instances where some really profound memories have been recalled within participants, whom have ranged from young children to elders. Once with a group of Central American women in the MacArthur Park community of Los Angeles, an elder recalled an impactful memory from her hometown in Guatemala. In this memory she shared with the group about a corn festival and ceremony her community used to practice when she was a child, but since then the tradition had stopped due to the disruptive effects of alcoholism in her community. When I led this activity with my own family, my maternal grandmother recalled that her mother used to make corn husk dolls. These memories, although just small glimpses into history, have the power to transform. I am curious about the possibilities of integrating these memories into our daily lives. What if corn festivals were revived in said community; what if my family continues the tradition of my great grandmother’s corn husk dolls? Recalling Patrisia Gonzales’s comment on the colonial project and de-indigenization being reversible, she reminds us that the power to re-tell our stories can regenerate our sacred relationships that were severed through colonization. Cherrie Moraga, Xicana feminist scholar, reminds us that “We are future and past at once,” and asks us, “So how can the re-collection of cultural memory as a strategy for future freedom be reduced to nostalgia? Does remembering not perhaps instead offer the promise of a radical restructuring of our lives?” (2010, p. 93). I trust that the arts are a wonderful starting place to ignite the psychological and psychic decolonization process, with the power to awaken the ancestral mind. Communities rebuilding relationships with their ancestral medicines, like corn, through collective storytelling and experiential learning can cultivate intuitive knowings that can inspire truly transformative visionary change.

References

Aveni, Anthony. (2001). The Historical, Ethnographic, and Ethnological Background for Native American Astronomy. Skywatchers of Ancient Mexico. University of Texas Press, 12-48.

Aveni, Anthony. (2001) The Mathematical and Astronomical Content of the Mesoamerican Inscriptions. Skywatchers of Ancient Mexico. University of Texas Press, 12-48.

Bonfil-Batalla, Guillermo. (1996). De-Indianizing That Which Is Indian. Mexico Profundo: Reclaiming a Civilization. University of Texas Press, 41-58.

Cajete, Gregory A. (2020). Preface. Native Minds Rising: Exploring Transformative Education. JCharlton Publishing Ltd., viii-vxii.

Freire, Paulo. (2000). Chapter 2. Pedogogy of the Oppressed. The Continuum International Publishing Group Inc, 71-86.

Gonzales, Patrisia. (2012). Ceremony of Return. Red Medicine: Traditional Indigenous Rites of Birthing and Healing. The University of Arizona Press, 211-228.

Howe, LeAnne. (1999) Tribalography: The Power of Native Stories. Journal of Dramatic Theory and Criticism, XIV(1), 117-125.

Lara, Everardo. (2013) Counts related to the human beings and the ceremonial count of maize. The Nepohualtzintzin within nahuatl figurative mathematic model. ACUDE.AC, 43.

Moraga, Cherrie. (2010). Indígena as Scribe: The (W)rite to Remember. A Xicana Codex of Changing Consciousness. Duke University Press, 79-96.

Rodriguez, Roberto. (2014). Prologue: The Ants of Quetzalcoatl. Our Sacred Maíz Is Our Mother: Indigeneity and Belonging in the Americas. University of Arizona Press, xvii- xxvi.

Seler, E. (1904). Venus period in the picture writings of the Borgian Codex group.” Bureau of American Ethnology, 28, 325-338

Smith, Linda. (1999). Twenty-five Indigenous Projects. Decolonizing Methodologies. Zed Books Ltd., 143-164.